In 2018, I visited Wesleyan University to see their Glyptodon in Exley Hall and instead found a stunning cache of historic relief models that are truly significant in the history of cartography.

Here’s the campus newspaper article about my visit: http://wesleyanargus.com/2018/04/23/mccalmont-places-universitys-relief-map-collections-within-campus-global-histories/

BACKSTORY

Edwin Howell, who designed and built the models on this blog, set up the Judd Hall natural history museum at Wesleyan University. Orange Judd Hall was built in 1870 from an alumni donation when the need for campus expansion in the sciences and buildings was great. Mr. Judd worked in agricultural sciences. He was contacted by Henry A. Ward to consider a large museum collection of fossils, rocks, skeletons, and other biological specimens that would fit the grandness of the building. Judd bought the argument and ordered a grand display of dinosaur skeleton casts, crystals, fossils, and maps.

Wesleyan in 1870 was at the leading edge of a great wave of museum building in the U.S. that lasted well into 1910. The public could not get enough. Today we would call it “outreach” by a university. But Wesleyan also was midstream of changes in the WAY science was being taught–new methods, theories, and ideas. Wesleyan wanted to attract the best students, and give them the best range and depth of science possible.

Edwin Howell was Ward’s brother-in-law and chief preparator of large museums. When I came to Wesleyan in April 2018, I had been transcribing the daily diaries of Edwin Howell, and so knew day-by-day how the collection was constructed and installed on campus.

Here’s the timeline.

- Monday November 28, 1870: “Have been at work on Meg. scapulae today. This evening have worked on cast lists.”

- Tuesday November 29, 1870: “Finished Meg. scapulae today and worked on legs etc. This evening have completed list (Judd cast) with Prof Rice and have been talking with him for two hours about things in general.”

- and so on

WHAT DOES WESLEYAN HAVE?

WHAT DOES WESLEYAN HAVE?

Here’s just a sample. You really have to see them for yourself!

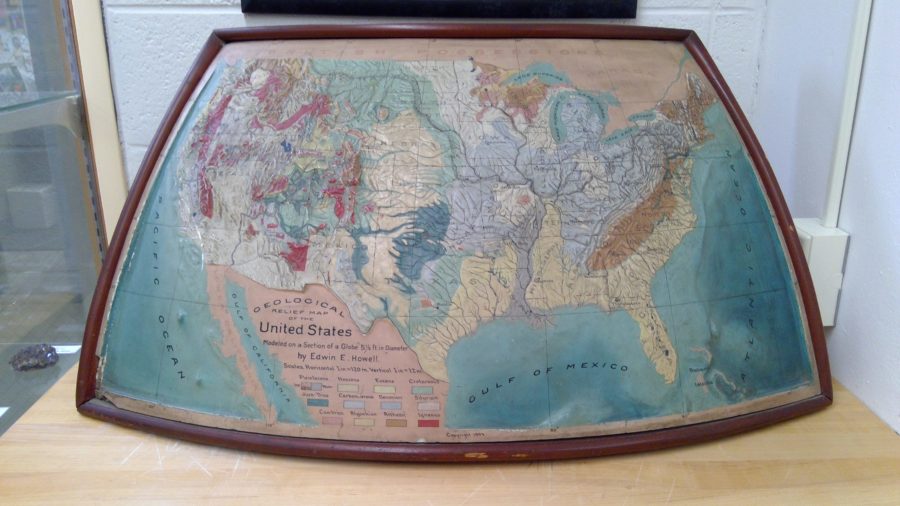

- An 1894 curved Howell tabletop US model, the first time students would have visualized the earth “from space,” something that was a critical intellectual moment for earth science students. Now we take this perspective for granted. It’s geologically colored, 120 miles = 1 inch, vertical exaggeration 10x. I mention this vertical scale because when teaching with model in 1900, the teacher would compare the tiny height of the Rocky Mountains on the surface with the depth of the ocean in the right corner. It’s a beautiful historic example of the first attempt to realistically geovisualize the US using large government data sets.

- Wesleyan has a copy of the very first commercial relief model in the U.S., “The Grand Canyon of the Colorado” built for them in 1877. But this was a LATER addition to their models for students.

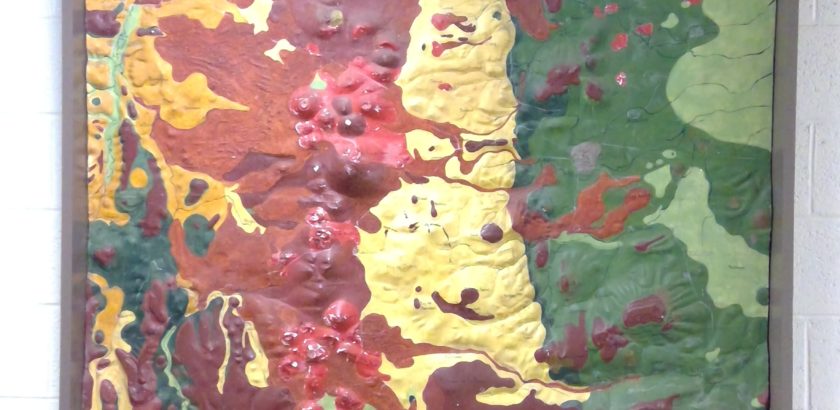

- An 1838 map of Mount Aetna that was part of a set of French relief models by George Poulett Scrope, used to press a new scientific theory about the way volcanos and lava work, how they change the earth. (The Wesleyan model has been overpainted and has lost much of its original detail.) Howell was making copies of Scrope’s model in his Rochester shop for sale to newly-emerging colleges and institutions.

- Ward & Howell small fossil collections, minerals, crystals, rocks, and even a stuffed buffalo from the day.

- A set of anthropological Anasazi Cliff House ruins cast as a set. First cast for the Central Park Museum, Wesleyan bought and maintained their set in near-perfect fashion. Remember that “anthropology” was a new field at that time, still called “ethnology” but with a dedicated group of educators who worked to preserve and honor the ancient cultures.

- The featured image at the very top of this article is the Puy du Dome region of Central Frame, again a Scrope model. This model was so controversial in its time! (The Wesleyan model has been overpainted and has lost much of its original detail.)

WESLEYAN IN THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE.

What was happening in society from 1860 to 1920 that sparked this swell of interest in natural science museums?

Science was acquiring new data and methods rapidly, just like it is today. In addition, the final struggle to separate science vs. religion was underway with theories of evolution. There was a HUGE need for examples, understanding, context, and method in a national system whose stated goal is free education for all children. Science teaching also wanted to be USEFUL, used for innovation, to invent photography, electricity, refrigeration, land surveying, and medicine.

In the history of science in particular, Ward & Howell relief models and collections supported 4 important social changes:

- Classification – Intellectual stress causes social stress, and humans respond to the chaos by trying to classify, organize, and document. Back then, the response was natural science museums. In our era, we call it public libraries and The Internet.

- Understanding the scope of US resources and human migration/settlement

- Evolution (time+change+biology)

- Professionalization of teaching, and access to college by middle classes

THE MODELS TODAY.

The Wesleyan Museum had a resurgence of interest and money in the 1930s, but eventually the pressure for space caused it to fracture and pack up by the 1960s. The collection was stored, exchanged, and sometimes lost. The Joe Webb Peoples museum was set up in Exley Hall (also worth a visit!!) To Wesleyan’s credit, I had many conversations with campus administrators and leaders about how to preserve and take advantage of the models and collections.